It had to happen some day. Some day, Sachin Ramesh Tendulkar would stop doing what he had been doing for 24 years and would retire from cricket. He would walk back from a 22-yard strip of grass and gold, only this walk would be longer and lonelier than the others. There was nothing anyone could do about it.

Except

say thank you in person.

Many

summers ago, when he was a different Sachin – young, brash and fearless (and we

were like him) – my best friend and brother Daddu, and I had vowed that if Sachin were to ever give the world a

heads up about retiring, we’d be there. No matter what was happening in our

personal or professional lives. It’s a big promise to make, and it almost

proved too big to pull off. But luckily, only almost.

We’ve

been known to have XXL mouths, but so far we’ve managed to avoid putting our

feet into them. Like the time we said (after Kargil) that should India (read

Sachin) ever tour Pakistan, we’d be there. Some 15 of us made that earnest pledge,

but only the two of us kept it. You can read about that here, but it’s

another story.

Promises

– even crazy ones – are easier to pull off when you’re younger, unmarried and

lower down the corporate pecking order. The advantages are obvious. You won’t

be missed as much at work. There’s lesser at stake personally. And as you’re a

foolish 23-year-old, the world will be indulgent towards you having a passion

other than passionately earning your EMI. But throw in words like Creative

Head, Biggest Pitch Ever, Home Loan, Family, Child and suddenly passion can

take the appearance of Don Quixote charging at the windmills.

At

times like these whom you’re married to (if you’re married) makes all the

difference. My wife, that lovely woman who doesn’t understand my craze for

Sachin but understands me, gave me the permission to get fired, should things

come to that. And so wearing a bravado that was more borrowed than ballsy, I

made my plea to my bosses. I wouldn’t do injustice to The Biggest Pitch Ever

but I had to be there at Wankhede. Otherwise, I’d end up hating my job and

would never forgive myself. I wasn’t given permission to go but to take a “call

as an adult”. I headed to the airport. It was the 13th of November

2013.

Now, going to Mumbai and going to Wankhede are two separate things. Especially if Sachin is playing for the last time. Tickets were harder to get than a one-line speech from Manmohan Singh, and we had nothing in our hands at the time of flying out.

But

leads were aplenty. I had contacted an ex-colleague who has access to both the

MCA and Vengsarkar, and he was confident. Then another friend’s wife, who works

at a leading newspaper, was trying her best to get us two tickets. My ex-junior

and not-ex-brother Shashi called me on his own and said he’d do something for

us. I also called and spoke to Vinod Naidu – Sachin’s agent whom I now know

over the course of so many ad shoots – and he said he’d try. I toyed with the

idea of calling Sachin –I have his mobile number for a while now – but as I’ve

never called or texted him out of respect, I didn’t want to start now. You can

gauge the desperation of my efforts by the fact that I even tried logging on to

kyazoonga.com a few times.

Daddu

too had his contacts. But our sources came and went. “Confirmed” tickets suddenly

got unconfirmed, and the only thing that was certain was that the two of us

would land in Mumbai and would be watching the match together – be it only on a TV screen.

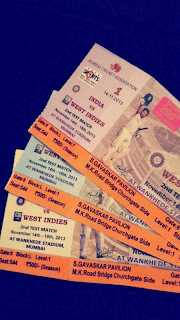

Then

magic happened. Late at night before the day we were to fly out, Shashi said that

two 5-day season tickets had been arranged for 10K apiece; did we want them?

Does Stevie Wonder need a break from Stevie-Wonder-jokes? They were for the

Sunil Gavaskar stand, and originally priced Rs. 500 per season pass. But given

that the going rate was 40K per ticket – if you could find a seller that is – we

said “yes” faster than Shoaib Akhtar running down a fat pickpocket.

Daddu

landed before me and collected our passes. I met him at the Grand Hotel, Ballard Estate,

where we had booked a room for a night. Let’s

say that the hotel had somewhat exaggerated their credentials, but the loo was

clean enough and the bed manageable. And the tickets in Daddu’s hands made us

feel like we were staying at the heritage wing of the Taj.

14th November 2013 dawned early and we were at the stadium gates at 8 for a 9am start. But even though it was a Friday and a working day, the line was longer than Mayawati’s handbags stacked in a row. But enterprising as we are, we requested a couple of youngsters at the very front to let us join them. And just like that – we were amongst the first 20 to enter the stadium!

The second happy moment happened when our tickets dutifully beeped at the entry turnstile (there was a slight apprehension that they might be fakes as we had heard some reports from the match at Eden Gardens). As we ran up the stairs, we saw yet another sign that nothing could go wrong with this trip: Sachin was warming up right before us, right in front of our stands.

As

the old chant of Saaachin Sachin left

our lips with a new desperation, he turned and waved in our general direction.

We took our seats and realized that our view was better than what we’d hoped.

We were expecting to sit behind ‘Point’ – a veritable blind spot as everyone

knows – but as the stand stretches and curves, our seats ended up being closer

to Extra Cover. Also we were at the right height – not low enough to feel the

wire fencing on our faces and not high enough to feel like the MRF blimp. Our

seats were also in the shade, a fact that we appreciated as we saw the poor

sods in the opposite stands getting suntanned for free.

A

word on the crowd then. The bleachers were getting filled even as our throats

were getting hoarse, and it was a beautiful sight. How do you explain a

45-year-old woman sitting all by herself in a plastic seat under an indifferent

sun? She was neither cool looking nor coolly dressed, just a middle-class housewife

who must have packed her husband lunch and seen her kids off at the bus stop,

and then taken the train quietly to Churchgate Station for a man who was

neither spouse nor child but perhaps at that moment, something more. Or the

old men at our hotel, 60 something to a day but happy as children

trick-or-treating. They had flown all the way down from England, leaving their

wives behind, one last boy trip for the love of a boy who had realized after 24

years that he was too old to play. There were many others. 10-year-olds too

young to be inspired but old enough feel the magic in the air. Infants hoisted

on shoulders, the day a blur but who would later find themselves in a

photograph taken on a cheap mobile phone, and point themselves out with pride

and a claim to memory. Most people looked like they didn’t know anyone

influential, but the ticket stub in their pockets showed that they knew how to

get in. Sachin’s family was there too. His mom was watching her son’s first

match, and brother, wife, kids and Achrekar sir, possibly the most loved coach in

world cricket. There were also the bigwigs – politicians, businessmen and film

stars. But none bigger than a small man in white; lion tamer, gladiator,

conductor of an orchestra bigger than the sport itself.

For

that’s how trivial the match had become. You could have put Australia instead

of West Indies, and the crowd wouldn’t have known. All they knew, and all they

cared about was that Tendlya was

playing for India for the last time. Perhaps this is why tickets to the series

were harder to come by than the World Cup final ones – that was for India, this

was something more personal. Sachin had become the game, and the cricket– not Herculean

to start with – blurred from contest to context. It was like the crowd, some

35000 strong and so much louder than that, wanted Sachin to know how much they

loved him. A loud roar would engulf him from the stand he was fielding closest

to, and even if it were Shami bowling to Samuels, the chant would have his

name. At some point, the crowd asked for Dhoni to hand over the ball to Sachin,

and the Indian captain became a national hero when he obliged. When it was our

turn to bat – the Windies were all out for 182 – the crowd couldn’t wait for Sachin

to come. Tradition has been for the Number 3 bat to be greeted with applause on

getting out (as Rahul Dravid has admitted with grace and a wry shrug of the

shoulders), but today the crowd was rooting for Indian wickets to fall from the time the openers came to bat. Yet

somehow, it didn’t feel unpatriotic. It was just India making her priorities

clear.

Sachin

came to bat as Murali Vijay departed, to a West Indian guard of honor. As he

walked towards the pitch, Wankhede embraced him with the loudest cheer it had

to offer – a thrilled throaty and teary thank you. For even his welcome to the

crease had the inevitable overtones of a sendoff. This was not about being

greedy for more; this was about savouring what remained. Sachin joined Pujara

in the middle, with the trademark poke at the pitch, the rolling of the

shoulders, that unmistakable half squat and adjustment of the crotch guard and

the customary surveying of the ground. There was also something new. For the

first time, he bent down and touched the soil, seeking its blessing. And when he

took strike, the crowd stood on its feet like one man and the chant, delirious

and deafening, swirled like dust in a bullring. Every forward-defense was met

with a loud roar, as if it were a six hoisted into the stands. Every bouncer

was faced with loud boos, the crowd indignant at the bowler for daring to bowl a

perfectly legal delivery. The mob – for that’s what we were – also grew

inventive. The regular Saachin Sachin gave

way Saaaaaachin Saaaaachin, a slow

hypnotic drone designed to conserve energy and get the wind back into the

lungs. And in the middle of it all, Sachin, unmoving as god in a temple, was

not only unaffected by the chaos but inspired by it. As the cover drives started

booming, the straight drive stepped out and the paintbrush flicks dabbed the

outfield, the crowd, incredibly, found a higher decibel. Wankhede started out as

a carnival, turned into a riot and then became theater as Sachin found his

timing and pushed the clock back. But when Pujara got strike, the crowd sat

down in one synced step and rested their bodies. It was so silent that you could

have made a conference call and lied to your boss about being out for the

match. If you were Pujara, you could have lied to yourself about being at the

match – such was the contrast between the ends.

Sachin

ended the day at 38 not out, and the crowd left, delighted at what they’d seen,

thrilled about what was to come in the morning.

Daddu

and I had found a new hotel as we’d checked out of the Grand Hotel thinking

we’d stay with friends to save money. But as I had to work for that almost-employment-ending pitch, we figured a quiet room might be better. The Regent Hotel

seemed like a good choice; it was close to Wankhede and closer to Leopold. And

so after a burpy-lunch, we trooped in to check for rooms.

The

hotel was unique, to say the least. It was almost like we’d walked into a

wormhole and into Riyadh. The ‘no smoking’ signs were in Arabic. In the lobby

were sprawled 4-5 Arabs in their traditional dress, in the midst of what

appeared to our conditioned minds as the Jihad Conclave 2014. The rooms were

nicer than those at the Grand, but the TV feed was entirely Arabic (till Daddu

discovered the Indian channels on pressing the video mode). And for two happy vegetarians,

there was not even Dal on the menu,

but the poetically potent Mutton Nasif.

Daddu

crashed, and I sat down to work.

Some 6 straight hours later, I thought I had cracked something nice, and we

stepped out – out into India – for dinner.

Day

2 of the match then. I reviewed the work sent by my juniors and we still

managed to reach the stadium gate at 7.30 a.m. After a hasty but hearty breakfast

at the Khau Galli close by, we

entered Wankhede. By 8.45, the stadium was largely packed, and heaving with

collective anticipation. The teams took to the field, and Sachin took guard

once again.

And

once again, he was the Sachin of old. The Sachin not only of yesterday but of many

yesterdays. That still head, the decisive footwork, the preternatural sense of

what the bowler was thinking, and the resultant extra time to choose the shot. And

just like that, inside the hour, he had raced to his 68th Test half

century. There were also a few misses, like the upper cut he tried off Tino

Best. But it was the missing-of-old, when Sachin missed while trying an

aggressive shot. During the change of overs, he patted Tino Best and the big

man smiled, delighted like he had picked up a five-wicket-haul.

That

was the loveliest part of it. Sachin played not like a grafter, an accumulator or a

senior statesman, but like the boy we had fallen in love with so many years

ago. He got out for 74, abruptly, unexpectedly and anti-climactically – to a boyish,

intent-laden cheeky cut that didn’t come off. And as a funereal hush descended

on Wankhede, it was like the curtain falling on our childhood.

Sachin

began the walk back to the dressing room, alone with his thoughts, perhaps not

realizing that a second innings was unlikely. In the meantime, the crowd –

acutely achingly aware – was at its loudest, as if hoping the clamor might stop

him from leaving the field. Just as he was about to cross over the rope, he

stopped, turned and raised his arms in acknowledgment. And then he was a small

figure walking up a long flight of stairs, and then he was gone.

The

giant screen kept showing Sachin’s last trudge back, and the match on the field

stopped as the crowd applauded once again. Pujara made a well-deserved hundred

and Rohit Sharma a fluent one, but the crowd was baying for Dhoni to declare.

We left immediately after Sachin got out; the India-West Indies series had started.

We

went to Pizza by the Bay, for umm…pizzas. The tables were filled with

fans like us, and every 5 minutes, an impromptu scream of Saachin Sachin would break out. We saw the same as we walked past

other restaurants – a pure, unadulterated, un-orchestrated outpouring of love.

And loss.

Day

3 began on a solemn note, the realization of not seeing Sachin walk out to bat

had long settled in. But he was still there on the field, and for now, that was

enough. If anything, the crowd was louder, fresh after a good night’s rest and determined

to make the most of every Sachinstant.

Dhoni threw him the ball again, and for two overs, the stadium sounded like

Sachin were batting.

But soon

it was all over, and it was over too soon. The West Indian wickets fell in a tumble,

almost like their batsmen had laced their shoes together. The Indian players

exulted, Sachin grabbed a wicket as a souvenir, and the moment started to dawn

on all of us. I daresay it dawned on everyone in the middle too. Dhoni issued a

terse order and the team formed a rolling, mobile guard-of-honor as the players

left the field.

I

think there was a presentation, a ceremony where someone picked up some award

and something was said. Everyone had eyes and ears only for Sachin. The

politicians tried to look puffed and important as they handed out mementos, and were booed as their names were

taken. And then Ravi Shastri, that crisp commentator of clichés, said his best

words ever: “Sachin, over to you.”

How

does one describe what has been seen by all? Sachin, surrounded by his wife and

children, walked up holding a sheet of paper. He tried to speak but we would

not let him. We too had so much to say. And so we chanted his name like we had

never said it before, we clapped like these weren’t our hands, all in hope that

we could tell him how much he meant to us.

And

then he spoke. For a shy, intensely private person, for a man of few words, a

20-minute extempore speech was a masterful effort. With a choked voice and wet

eyes, Sachin thanked all those who had played a role in his cricketing

career. There were no big words, but there were beautiful ones. Like referring

to wife Anjali as “the best partnership of my life” and telling us that “Saaachin Sachin would reverberate in my

ears till my breathing stops”. It was a Sachin Special; he had saved his best

for retirement day.

But Wankhede wanted more, and got more. Sachin did a lap of the field – hoisted on the shoulders of Dhoni, the Indian Captain and Virat Kohli, the legatee – waving the tricolor to a bedlam of chants, claps and cries. It was indeed a champion’s farewell.

But

it couldn’t be over with just a public goodbye. Sachin’s last act on the cricket

pitch was to walk back alone to the 22-yards that had given him everything, and

say thank you. More student than master, like he had always been.

We

advanced our tickets and flew back home, to our wives, kids, EMIs and jobs

(yup, I managed to hold on to mine). We felt empty but not as empty as we’d

thought we would. Being there at Wankhede and the three days of sustained high

emotion had been catharsis, and more importantly, closure. We felt like Dr. Seuss when he said: “Don't cry because it's over. Smile because

it happened”.

To

those who throw around big phrases like Impact Index, we have this to say. The true

impact of a player on sport is beyond stats and winning percentages. It is

about how you affected the game itself. About how you inspired a generation to

pick up the bat and taught another how to forget their burdens. It is about how

brightly you shone in the dressing room even as a fading light; while at your peak you were the sun itself. It’s about how you commandeered not just

grudging respect but gushing praise from the very best you dueled with. It is

about how you got an entire nation to start, stop and work its life around

yours. It is about how much happiness you gave, by the mere act of being there.

So

thank you, Sachin, thank you for more than just the cricket. In a world of

fickle fans and fleeting heroes, your poster on our walls shall stay. As will

the 10 tattooed on our wrists.

Saaaachin Sachin!

Ram

Cobain & Gaurav Dudeja

16th

November 2013

.JPG)

.JPG)